Scholar Shan and His “Chinese Yard”

“A Reading Lover Who Reads Few Books”

Hegezhuang sits between the Beijing-Chengde Freeway and the Jingping Freeway outside the North 5th Ring, far away from downtown Beijing. Walking along the messy streets, we enter the secluded No. 55 Art Space through a wood door, discovering a marvellous place.

A Wood Door Connects Two Realms

Liu Shan, a generous and compassionate Aries, is the owner of the No. 55 Art Space. He is known as ‘Scholar Shan’ by the art world and nicknamed ‘Brother Shan’ by close friends. In recent years Liu Shan’s highly acclaimed The Study of Scholar Shan, The Tearoom of Scholar Shan and so on, have been displayed in different places.

Xu Tianjin, Professor of the Archaeology and Museology School of Peking University and renowned archaeologist, says that Scholar Shan is a man who lives an enviable life: ‘His daily routine is enjoying delicious cuisines and fine arts’. The ‘Kitchen of Scholar’ satisfies his stomach, while the ‘Study of Scholar Shan’ pleases his eyes and ears, so ‘he enjoys a satisfying material and spiritual life’.

The Tea Table in the No. 55 Art Space

The name No. 55 Art Space originates from the number of the yard—No. 55 of Hegezhuang. It also corresponds with the name of his gallery, Wu Shi Wu (‘I know myself’), which means ‘renewed self-recognition at the age of 50’, said Scholar Shan. Before 50, Shan engaged in the logistics industry for years as a senior executive at a Switzerland-based international logistics company, but even then he had a passion for collection.

Yard of No. 55 Art Space

Yard of No. 55 Art Space’s Interior

Resembling quadrangle dwellings (a typical Beijing residential architecture), the yard of No. 55 Art Space is serene and antique, with an exhibition room, living room, tearoom and dining hall on the first floor and a study on the second. This is where the owner works, meets with friends, studies and practices Chinese calligraphy and indulges in contemplation. Every room reveals the interests of the owner and his pursuit of a wonderful life. Simple and comfortable, the details of the interior are also avant-garde and modern in a natural way. Scholar Shan perceives it as a secluded area for gatherings and chats over tea; as he says, ‘it is actually a gallery that resembles private space’.

A diversified range of collections found in all corners of the No. 55 Art Space are integrated with the living space. Scholar Shan has built the space as a mixture of Chinese-Western works from all time periods with years of life experience and aesthetic comprehension. He notes, ‘What I attempt to stress, between the gallery and private living space, is how to make artworks you buy fit in your house naturally and what their relationship with the owner is’.

Tearoom of Scholar Shan

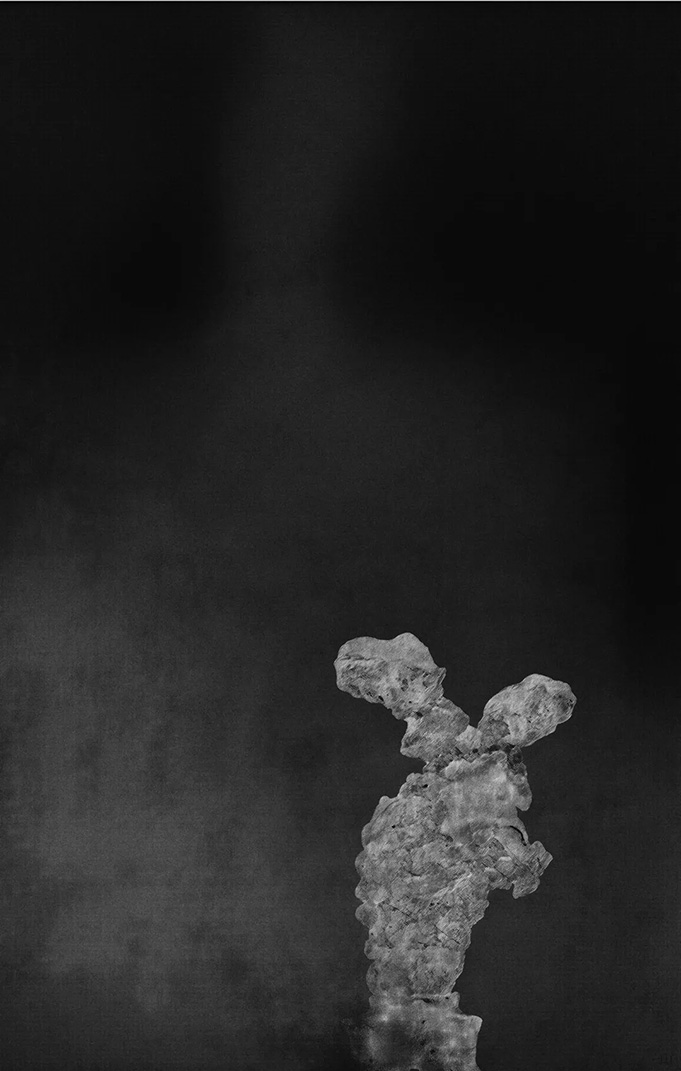

The Beijing Rocks Reimagined/Hans Fonk Photo Exhibition was staged at the No. 55 Art Space not long ago. Hans Fonk, the founder of OBJEKT magazine and a publisher, was formerly known as a famous fashion photographer and is now an artist. His photos demonstrate two different facets of contemporary China—traditional and modern, as well as unique and splendid.

A series of ‘mixed’ exhibitions and activities had been held in the Space before this: the Tearoom of Scholar Shan, which is mainly decorated with ceramic works and lacquer wares by, respectively, the Japanese craftsmen Kosaka Akira and Totoki Akiyoshi; the ‘Amidst Ink-Wash Memories—Shen Qin Solo Exhibition’, co-hosted with the Hong-Kong-based Lam Gallery; the ‘In Marking Moments—Solo Exhibition of Xu Jing’, who is a contemporary Chinese calligrapher; and ‘Roaming between Scribing and Calligraphy’, which displayed works by Chen Danqing, Hans Hartung and, Lumi Mizutani. As Scholar Shan advocates, the Space ‘sees no boundaries between the past and the present or between different nations’.

Photography Beijing Rocks by Hans Fonk

Scene of “Beijing Rock Reimagined / Hans Fonk Photo Exhibition”

Study of Scholar Shan: A Bookless Study

If you had the opportunity to walk into the No. 8 Exhibition Hall’s ‘Brush, Ink, Paper and Ink Stone—Form and Imagination’ at Guangdong Museum of Art in July, you would have seen the exact copy of the Beijing-based ‘Study of Scholar Shan’. Scholar Shan shared his study-like living space and life practice with the visitors to the museum, presenting a vivid and ongoing contemporary living field: ‘The space is an attempt to build a bridge connecting art with life’.

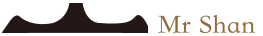

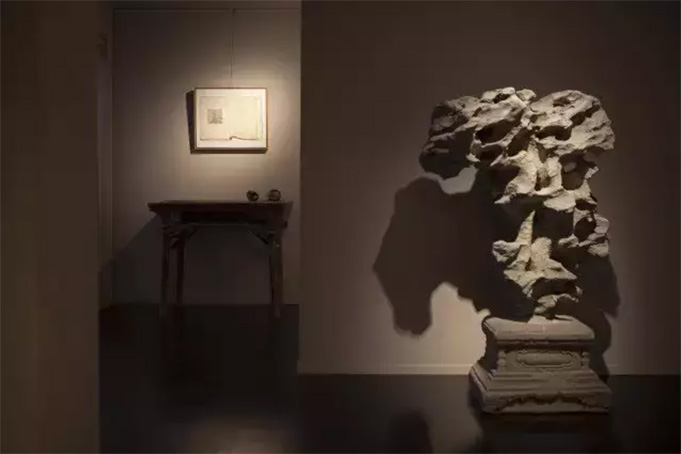

“Study of Scholar Shan” in “Brush, Ink, Paper and Ink Stone—Form and Imagination” at Guangdong Museum of Art

The ‘Pine Tree Series’, an installation by Shi Jinsong, is put on Bimodal Stone of Taihu; ‘My Solitude Is A Garden’, a light box installation by Liu Lingzi, shines light on Xu Jing’s work ‘Chen Nian’.

Pine Tree Series by Shi Jinsong Bronze & Lacquer 180×146×233cm 2018

Calligraphy Work by Xu Tianjin 37×140cm 2017

My Loneliness is a Garden (series) by Liu Lingzi 150×180cm 2013

Upper: Recognition Device-2 by Sun Xiaofeng Ink-Wash Painting 55×138cm 2018

Lower: Prototype Sofa BO-48 by Finn Juhl Teak, Ash & Leather 140×66×83cm 1948

Upper Left: Bird-Shaped Container by Ke Ke Pottery 30×17×43cm

Lower right: Untitled by Gao Zhenyu Floral Vase H: 40cm 2014

Lower right: Arm Rest by Shao Fan

Right: One of the Works Pending A Name by Chen Danqing Oil-on-Canvas Painting 202×76 cm 2014

Left: Recliner W: 107 cm D: 64 cm H: 100 cm

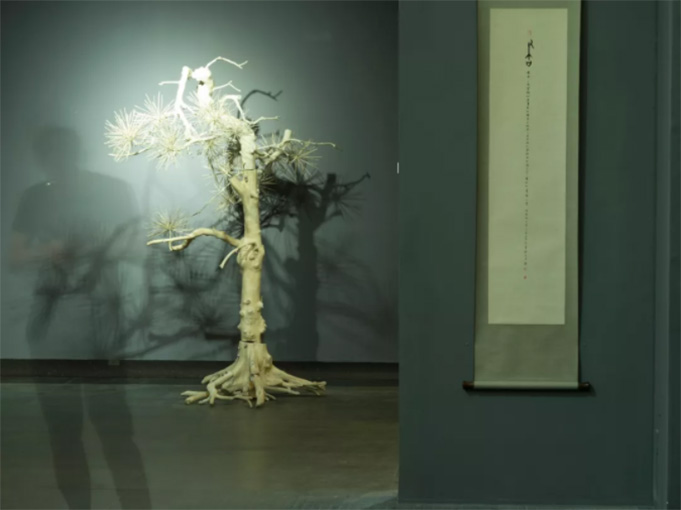

‘Restoration of A Rustic Life’ by Liu Dan, ‘Landscape 1711’ by Shen Qin, ‘Hua Jin Se’ (a series of three ink-wash paintings) by Yang Yanling, ‘Blind Turtle Meets the Floating Log’ by Chen Hui, ‘Recognition Device-2’ (ink-and-wash painting) by Sun Xiaofeng and the calligraphy work by Xu Tianjin—these works bring the decorative effervescence in otherwise tranquil space.

They are joined by the stainless steel, round-backed armchair by Shao Fan, ceramic works from the Nirvana Series by Gao Zhenyu, Calotes Versicolor made out of colourful agate stones by Pan Jingshi, ceramics from the Tea Ware Series by Kosaka Akira, the vintage camera bag by designer Kai Yi and Montecristo Deleggend perfume…It seems that the works have connections with each other and with daily articles and spaces, while they are independent in other ways.

Landscape 1711 by Shen Qin Ink-Wash Painting 97×174cm 2017

Some visitors commented that it was “the extreme of mixture”.

For Scholar Shan, the ‘Study of Scholar Shan’ is by no means a formalistic show, nor does it follow any fixed format. Rather, it starts from human needs and breaks through the differences and misunderstandings between Chinese and Western cultures. He observes that ‘It is hoped to demonstrate the jing (mind), qi (energy) and shen (spirit) of contemporary humanities and arts in works. As long as a work fits in the artistic atmosphere of the space harmoniously, the form does not matter anymore’.

Dwellings shelter us in the earthly world, and studies reveal the inner worlds of the residents. Every detail of the display speaks to the temperament of the owner. For Scholar Shan, the decoration of his study is based on the traditional colours of the five Chinese elements (metal, wood, water, fire and earth). As long as it is smooth and harmonious, it will work.

Every work in the study has a direct connection with Scholar Shan, but not in a contradictory way. For instance, an iron warrior helmet by Kai Yi aroused the curiosity of many people of the post-80s and post-90s. What touches Scholar Shan the most is the design, the production of the work and the artistic quality incorporated in it. ‘It combines fashionable elements with traditional Chinese elements. I’m moved by the artist. His works are marvellous’, said Scholar Shan.

Scholar Shan suggests, ‘A work that can touch people is an excellent one. It could be a painting or design, no matter [if] it is famous or not. Personally speaking, I’ll not judge a work by its market value’.

Iron Warrior Helmet by Kai Yi Comprehensive Materials 2015

How is a study related to each individual in an exhibition on ‘brush, ink, paper and ink stone’? As Scholar Shan puts it, ‘The presentation of the study is crucial to the life of modern people. In other words, it raises a question [about] how we can carry forward traditional Chinese culture’.

There is much talk about how to make life an art and how to bring art into life. Actually, art is already in our lives. You can carry forward traditions by enhancing our surroundings. Scholar Shan says, ‘I want to put forward a methodology for every visitor through such a presentation to help them find their own standards of design and aesthetic. Of course, you’ll have to achieve that by reading books, things and people’.

Xu Tianjin nicknamed Scholar Shan ‘a reading lover who reads few books’, and the study of Scholar Shan is indeed bookless. What he collects in his study is more about things. ‘Liu Shan is a reading lover who reads few books, and he has an elaborate study’. When you are there, you get to browse, observe quietly or even touch gently, just like reading. ‘Things are what he reads’.

In fact, his study has already risen to fame at the 2016 Beijing Design Week—Beijing Fun and Maison Shanghai. His study takes on Scholar Shan himself and the new lifestyle he represents as core elements to build a space brimming with traditional artistic atmosphere and contemporary spirits with the functions of studies at its core.

For the art sector, in turning down ‘antique’ forms and upholding the aesthetic theory of ‘mediocre’, the ‘Study of Scholar Shan’ has somewhat reproduced the delicate life of ancient Chinese scholars as well as acted on solutions to the lifestyle of contemporary Chinese people.

It Takes A Family to Make a Collector

The concept of the ‘Study of Scholar Shan’ originates from his involvement in art collection.

In the 1980s, as he had some savings, he bought three ink-and-wash paintings by Lou Shibai on the recommendation of a friend. That was his first experience with collection. He bought a pair of blue-and-white porcelain wine vessels with RMB 300 at a China Guardian auction, after which he made weekly visits to the small China Guardian auctions. That was how his journey of art collection began.

Scholar Shan started to collect furniture in the 1990s for practical and decorative purposes. At a loss in the very beginning, he soon fixed his goals—large-sized beech furniture. According to him, it was partly because there was already a well-developed beech furniture industry in mid-to-late 90s, with reasonable prices. It was also because of beech’s relation with scented rosewood. Beech wood is the best representation of a craftsman’s personality, both in terms of design and style.

Rosewood Table

In the late 1990s, he started collecting oil paintings. Works by Liu Xiaodong, Ji Dachun, Chen Danqing and Yu Hong are all in his collection. In 2002, he bought a representative painting of a face mask by Zeng Fanzhi at the price of RMB 45,000. Two years later, the price of that painting soared to RMB 600,000. He bought a work by Fang Lijun at an auction in early 2000 and sold it in 2007, and the money he gained from it became his investment in a photography collection.

Tower by Ji Dachun, once on the cover of Fine Arts Literature

Self-Portrait by Yu Hong

‘Self-Portrait’ by Chen Danqing, as well as his other works, constitutes the most complete series in Scholar Shan’s collection. He reports that ‘the current value of the painting is estimated to be hundreds of times as much as when I collected it’.

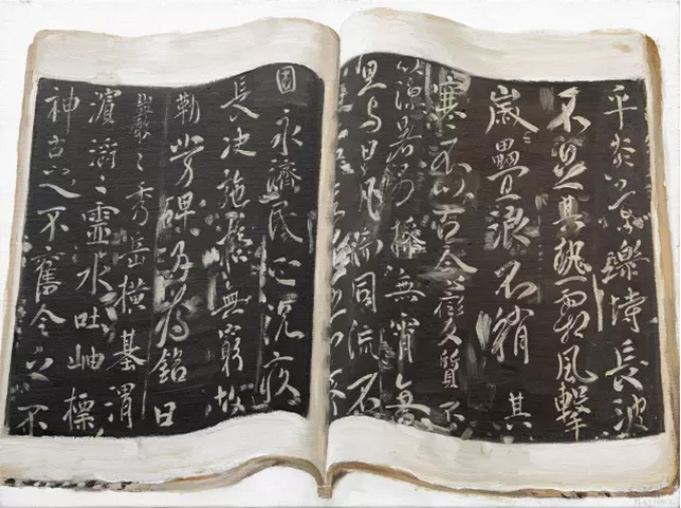

Book Early Still-Life Painting Series by Chen Danqing

Scholar Shan collects a wide range of artworks: contemporary oil paintings, traditional paintings and calligraphy, antique Four Treasures of the Study, contemporary ink-and-wash paintings, photos and furniture. The collection goes beyond China to cover many European masterpieces. Scholar Shan believes that when it comes to collecting, ‘he might have come at the right time with the right approach and met with the right tutors’.

Scholar Shan is quite close with Xu Lei, Chen Danqing and Acheng, who curated his photography collection. Xu Lei has the most profound insights in photography and the composition of pictures; Chen Danqing provides aesthetic guidance; Acheng conducts systematic and deep research on photography.

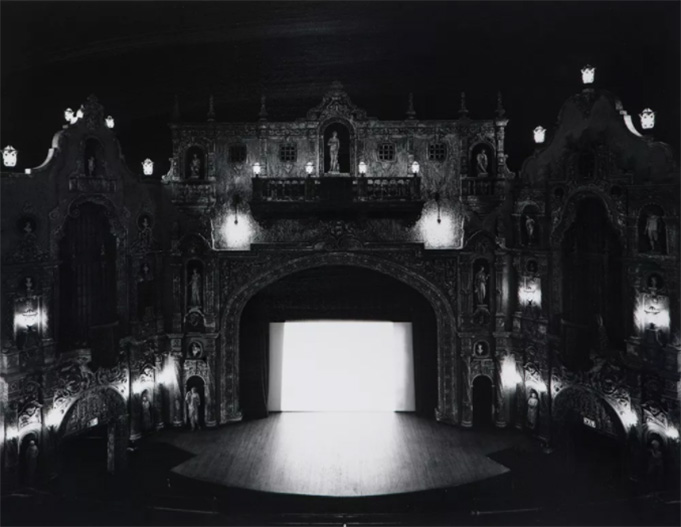

When contemporary Chinese photography started in 2000, Scholar Shan began to purchase works of world-class photographers from overseas galleries, such as those of Araki Nobuyoshi, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He also collected some domestic documentary photographic works, such as ‘Big Eyes’ by Xie Hailong. In his collection, there are works that could easily pass for museum pieces, such as ‘Florida Theater’ by Hiroshi Sugimoto, ‘Picasso’s Bread’ by William Klein and ‘La Dame Indignee’ by Robert Doisneau.

Florida Theater by Hiroshi Sugimoto

Girls’ World by Araki Nobuyoshi Photography 53×42.3cm 1983

‘I purchase artworks to build my living environment. As part of life aesthetics, artworks find [their] way in life naturally’, Scholar Shan says. He jokingly adds, ‘I’m continuously spending money. It is like a cycle. I spend the money earned from collection on collection’.

It is his family that makes him a real collector.

‘I’m not a collector. I buy it because I like it. Some are from China, while others are from abroad. It’s natural for me to use them in daily life.’ For the display of things in his space, the most important issues that should be considered are ‘relationships between things and people’. No. 55 Art Space was established to share things he likes and ideas that hit him in daily life.

There are no rules for displaying art, but it requires knowledge and insight.

Speaking of No. 55 Art Space, Scholar Shan laughs, saying he built it to store collections because his home and warehouse had no space for them anymore. When selecting European furniture, he has no special preference for any style. You can find the Baroque style as well as Gothic styles in his study. He will not be limited to certain styles or make any symbolic arrangement in decoration. As he says, ‘It is just taking people as the centre and discovering the relationships between things and people. Don’t be too hard on yourself’.

Western sofas, tables, contemporary calligraphy works and Japanese ceramics come together naturally

‘Running a gallery is definitely a money-losing business,’ Scholar Shan admits. For him, establishing the No. 55 Art Space was an attempt to pursue ‘a sense of existence’ of himself. He continues, ‘I have never done that before. It’s a vison of mine to live the rest of my life with it.’

‘I didn’t choose the 798 Art Hub in Beijing, because I’ve never taken the gallery as a purely art practice. It’s not about any art concept, either. I [just live] in this way. I bring my life into the space. It may be helpful to my business if I choose 798, but it will make no sense to my life’, says Scholar Shan.

For most beginners in the art world, art consumption and collection can be rather confusing. Scholar Shan says, ‘I show it in space that what I stress is the relationships among things, artworks and the people who live with them’.

My vision for No. 55 Art Space is that every artwork in it is directly linked to life and each of them can play their ‘practical’ role in daily life. ‘What I always emphasise is actually a consumption found between materials and spirits, covering all aspects of life—eating, drinking and playing. Yet, all of these are directly connected with aesthetics’.

Exhibition Space in No. 55 Art Space

Scholar Shan has always laid great emphasis on aesthetics, saying that ‘Art must be a process of barrier-free communication, which [is] directly linked to its value instead of price.’ However, domestic buyers tend to judge artworks by their prices in consumption, regardless of their value and relationships with people. ‘Artworks are not “practical” items in nature, but their value will be exposed once they are used; so are their relationships with people. It’s philosophical’.

Scholar Shan says that some artworks just could not ‘fit in’ his space, but it does not mean they are not brilliant. What he pursues is that a work is a perfect match with the space, be it Chinese or Western, ancient or modern. He tries to achieve unity and harmony in an artistic atmosphere by negotiating between space and things. This is what is meant by ‘There are no rules for displaying art, but it requires knowledge and insight’.

‘There is no need of imposing limits on display. You will be constrained by form if you take it as the core. You will only truly achieve spiritual pleasure and freedom when you break the shackle of form’, says Scholar Shan. For Scholar Shan, what is essential to display is ‘diversity in order and delicate simplicity’.

Tearoom of Scholar Shan

‘In fact, what you should learn is not about display but how to enhance your aesthetic level and [broaden] your horizon’, he adds. Scholar Shan points out that ‘Traditional culture is the underlying foundation of both oriental and occidental arts. You need to discover their relationships with people in real life’.

‘Your personality will be reflected in the space you design. It’s important to design one that suits yourself’, he insists. Scholar Shan believes that the fundamental approach to display is to start with colours, contents and furnishings and to discover the relationships between articles and between articles and space and users. He endeavours to integrate his works with life, saying, ‘I enjoy an exquisite lifestyle and aesthetic sentiment’.

Scene of the ART021 Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair

He continues, ‘I share with others a methodology, and, [in] the meantime, learn from others who have made a better match or display. It is indeed a process of mutual learning.’ Scholar Shan’s popularize the trend of mixing modern and ancient as a decorative concept.

From A Study to A Yard

At Christie’s Shanghai Autumn Auctions 2017, Scholar Shan designed a theme activity called ‘Contemporary Scholars’ Studio’, consisting of 30 cultural devices representing different scholars’ aesthetic tastes in life. They are contemporary art treasures and works from collectors or artists in China, Japan and the US, including furniture, bonsai, ink-and-wash paintings, jade ware, photos, ceramics, red porcelain ware and floral vases.

Scene of “Contemporary Scholars’ Studio”

Traditional Chinese space is not his ultimate goal. Instead, Scholar Shan has broken the categorical and geographical boundary of studies. ‘It is not a simple concept of traditional Chinese studies or the simple combination of Chinese and Western studies. Rather, it is an ideal, people-centred space.’

‘I’m not against traditions’, Scholar Shan argues. ‘On the contrary, I show high respect to traditions. While absorbing Chinese traditions, I’m also learning Western traditions. Eastern and Western cultural veins are the foundation of today’s study. Without traditions, it would be like water without a source.’ Scholar Shan notes that space is an expansion of life practice and an accumulation of time and experience. It is an ongoing process of learning and adjustment. If it has nothing to do with yourself, then you are doing it to show it to others.

Scene of “Contemporary Chinese Studies”

‘Brush, Ink, Paper and Ink Stone’ is not necessarily an exhibition that puts these items on display. What are their relationships with their owners? Scholar Shan answers, ‘To curate any space, one needs to consider your own ideas and standards. It must be connected to the owner. As to insights and aesthetics, it depends on your own efforts,’ he continues, ‘don’t fall for formalism in any work. It must be realistic. If it doesn’t deal with people, then it will be perplexing and thus separate itself from people’.

A Corner of the Tearoom of Scholar Shan

Over two decades of experience in life practice and art collection have all come down to the No. 55 Art Space. Be it the study, tearoom or kitchen of Scholar Shan, it extends experience and derives from experience over time.

This set of standards arises from the ideas of traditional scholars, the concepts of modern people, and, more importantly, life: ‘You will have to constantly experience it by yourself in practice and negotiate with space and then make [adjustments]’.

Scholar Shan hopes what he does ‘can bring an aesthetic value to people. I hope everyone can think about it from an aesthetic view while selecting his living space, or even selecting clothes to wear. As a matter of fact, it is a process of knowledge accumulation and aesthetic appreciation. Beautiful things are around you. Can you keep them in mind? Are you able to work with them appropriately?’.

Beauty Is around You

In recent years, as people are in reminiscence of traditional cultures, Chinese architecture has naturally re-emerged. The fusion of traditional architectural elements and modern techniques has given rise to the popular ‘New Chinese’ architecture as represented by ‘Chinese yards’ across the country. However, the majority of the so-called ‘Chinese yards’ are merely modelled on traditional architecture or the piling up of traditional elements.

‘It has nothing to do with life. Nor does it consider the relationships between buildings and people’, Scholar Shan argues. ‘Real estate agents are working in the right direction when they try to add arts and traditions to buildings, which proves they have begun to attach importance to aesthetics. It is the predominant trends’. In spite of that, brining art into life and recalling traditions cannot be achieved by copying. It must be ‘cultivated’. In other words, you should choose the one that suits you. That is the fundamental difference between copying and cultivation. Appropriation and blindly piling things up may lead to strange, unnatural and ostentatious buildings. Most ‘Chinese yards’ have fallen into this trap.

As indicated by Scholar Shan, a real Chinese yard should essentially be built on cultural heritage, while featuring the characteristics of the era with close ties to people in a contemporary context: ‘The key to a real Chinese yard is to take people as the centre. The architecture is the presentation, while home is the concrete object. People are the entity, the carrier and core of everything!’

Some Works of Partner Artists of No. 55 Art Space

Beijing Rocks by Hans Fonk

Calligraphy Copybook of Emperor Taizong of Tang II (Collotype-Edition) by Chen Danqing

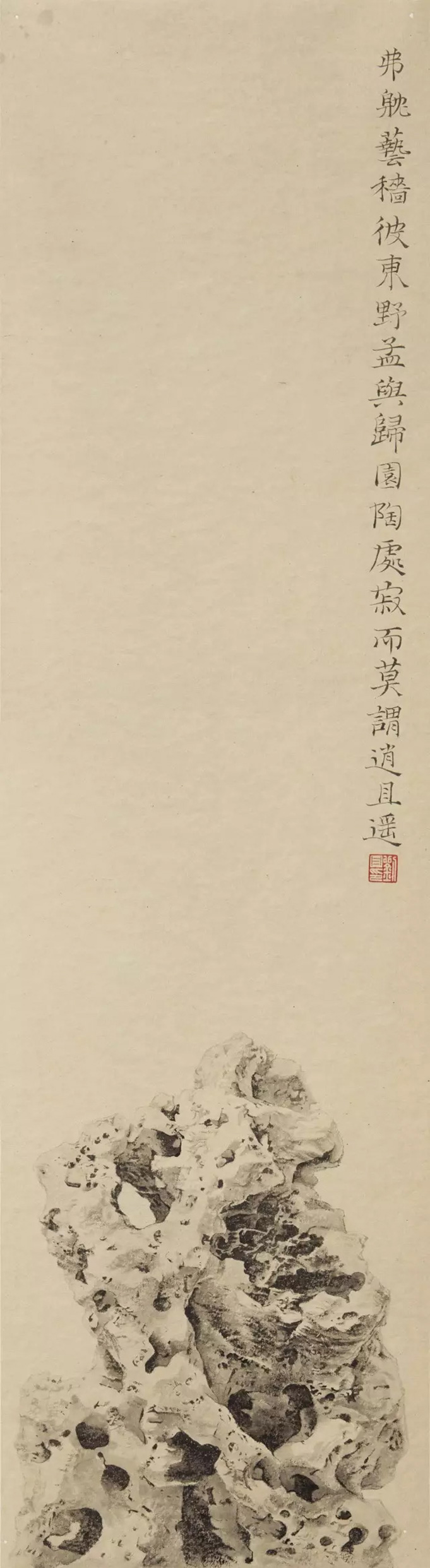

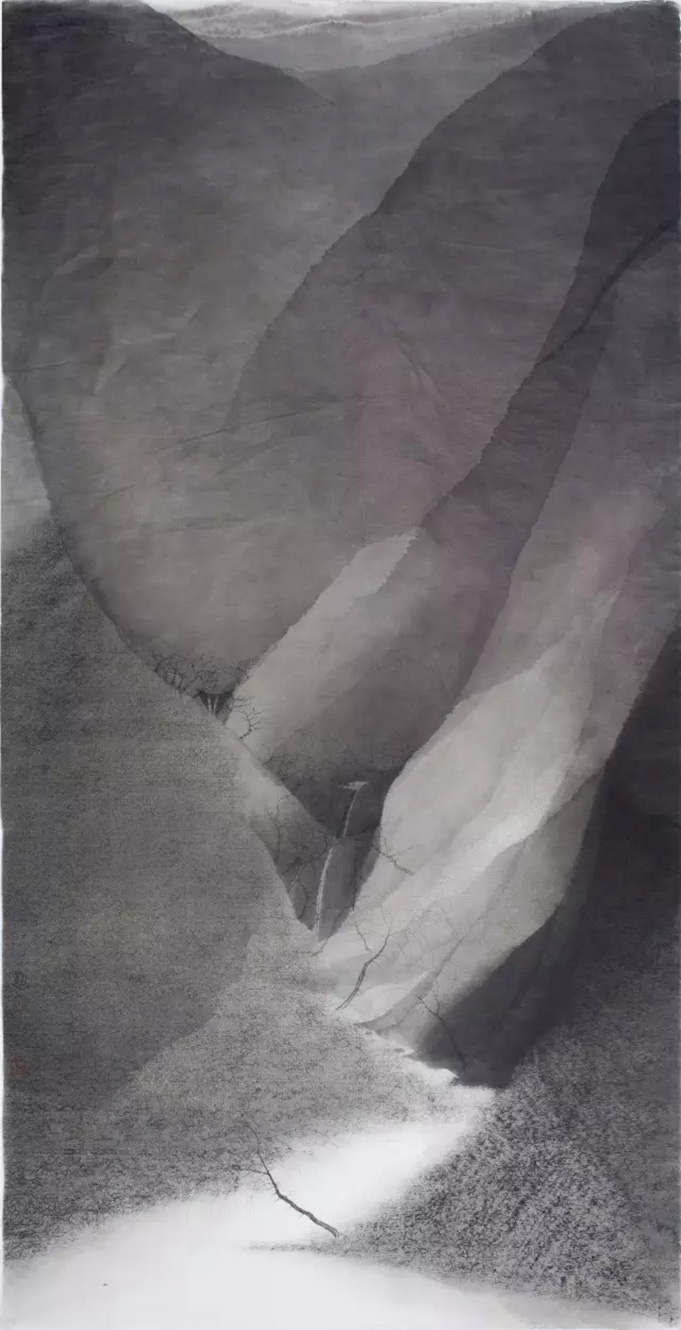

Restoration of A Rustic Life by Liu Dan

Lian by Yang Yanling

Wu Wu Xiang Ying No.66 by Sun Xiaofeng

Landscape after the Song by Shen Qin

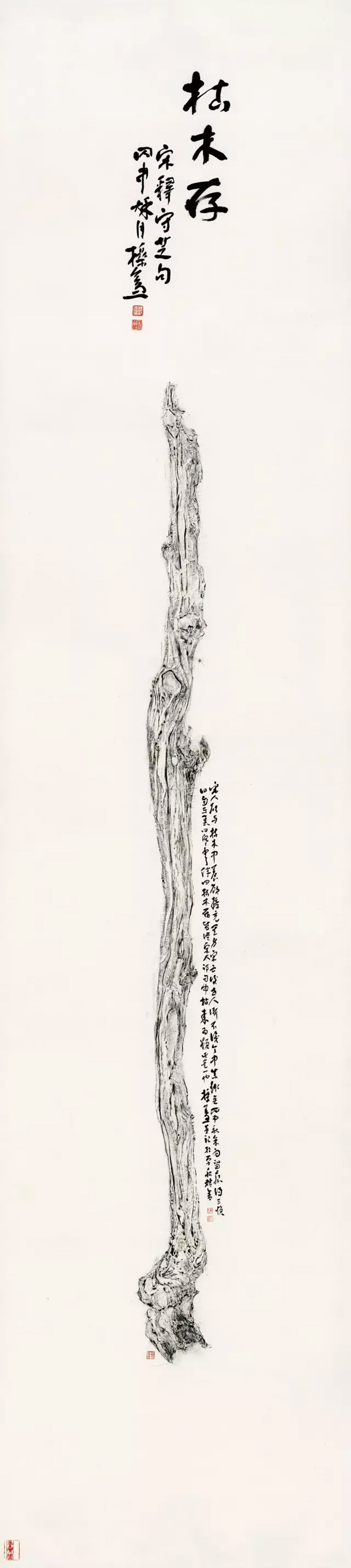

Jian Shan by Xu Jing

Floral Vases by Gao Zhenyu

A Yingta on Paper by Chen Hui