To wake up in the morning and be greeted by a 2000-year old totoro tree – even the renowned animator and cartoonist Hayao Miyazaki didn’t have such privilege!

‘To be a happy person, one needs a sea view, warm spring and flower blossoms’, said Haizi, a young Chinese poet. But what if you wake up every morning to the sight of a two-thousand-year-old totoro tree, living in the dream world that Hayao Miyazaki built, but you do not get to enjoy it? The person whose indissoluble destiny is with the totoro tree is Kosaka Akira. A master of pottery, an old urchin, Kosaka says he has only played with clay for 60 years!

The legendary dragon tree of Miyazaki Hayao is located 500 meters from Kosaka’s studio. People can climb the tree to its top. According to Kosaka, the tree is two thousand years old.

Who is Kosaka anyway?

Kosaka Akira is a master craftsman and professor of contemporary ceramics at Musashino University, where he has taught for 20 years. Tired of the busy city life, Kosaka and his wife decided to make a new life in the coastal town of Kochi. They built a house among the totoro trees, a safe haven where they could practice ceramic art. The twenty years have flown by.

In the city, we are subjected to the fast pace of life and its many pressures, and that’s why many people swap the impetuous city environment for a tranquil country life. An elegant house, the sunrise call to work and sunset call to rest, a warm cup of tea, fresh vegetables from the garden, the music of rainfall and meditative odours of agarwood incense, it all seems like a dream to many of us. But it is Kosaka’s life; the life of perpetual play with clay, the life of infinite creative possibilities. His ceramic art is his life.

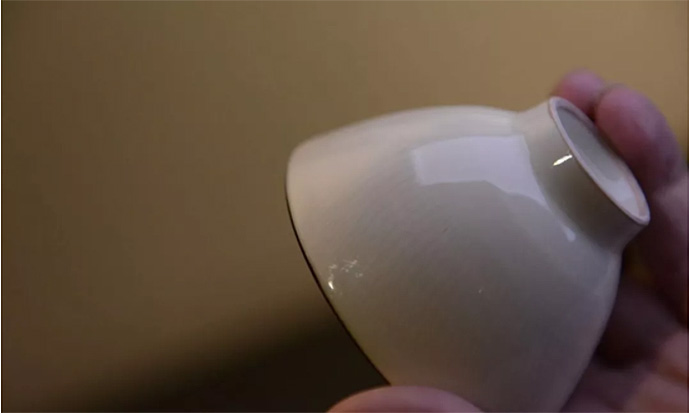

‘I am not an artist, and my works are not works of art. I make useful things for people’, he says – even while his cups are being collected by the Imperial Palace of Mikado.

Kosaka is an enthralling soul, one in a million. But what happens when two equally beguiling souls meet? Gao Zhenyu met Kosaka when Gao was studying at Musashino University, and that’s when their worlds collided. When Gao Zheyue shared the Yixing purple clay teapot techniques with Kosaka, he questioned him in dismay. ‘Why does a teapot have to be so perfect?’ Kosaka’s thinking stems from the Japanese folk wisdom of the unity of man and nature. The simplie feeling, or one of nature’s voice, permeates each and every one of his pieces. This debate between a teacher and a student set the stage for twenty years of friendship between the two ceramic titans. It also paved the way for Kosaka’s works to come to China.

Kosaka insists: ‘I am not an artist; I am a craftsman. My work is not artwork; it should be affordable for most people.’ His words are just as pure and sincere as his works of art.

Kosaka’s vessels came from life and are used in life. There is no obnoxious attitude of the art world, and there is no deliberate pursuit or performance ritual. There is only faithful transmission of his skills and nature for everyone to enjoy. Kosaka has no assistant in his studio. He completes every step of the process himself, making every piece one of a kind.

Vessels of this kind, no matter what they are used for, are always a joy to have!

Kosaka’s ceramics are full of composure, with their quiet but assertive power and sincere emotional purity. Each piece fits perfectly in life, as it has a multitude of functions, whether you have eating, drinking tea or a flower arrangement in mind. The urge to make only useful pieces not useless things, could have only come from a capricious man like Kosaka. Good vessels no matter what they are used for, are always a joy to have! These are things for life; they grow old with you, assuming your character and temper.

Mr Shan’s teahouse has a number of ceramics made by Kosaka. His favourite is the black lacquer teapot that has been with him for years. The shape of the teapot is like a full, bulging belly trying to tell you how much tea to drink. The spout of the teapot bows properly. The mouth of the spout shows Kosaka’s ingenious design. The micro expression on the body of the pitch-black teapot displays a surprising earthy halo. The soul of the object is not just the inner world of its creator but also the spirit of its user. Once Mr Shan had used Kosaka’s teapot, he wanted no other.

This may be the highest state of an artist’s life, but is it Kosaka’s philosophy of life?

What do others say about Kosaka?

‘The most representative depth and self-expression in works come from continuous learning. When you acquire understanding, you put them down, or even forget about your ideas. You just let them age in your heart. When the time comes, like a yawn or a stretch, selfless reveal can only do good for works. That’s what you get in Kosaka’s works.’ – Gao Zhenyu, China’s legendary ceramic artist

‘The pottery pieces are born with nature and breathe with time.’ – Xu Jing, renowned modern calligraphy artist

‘Sensibility is my first impression of Kosaka’s ceramic works. There are no excessive edges or deliberately designed curves that are uncomfortable. The pottery works are both dynamic and still.’ – Da Longkuan, founder of ‘Travel Master’ and travel industry veteran entrepreneur

‘One can feel the spirits at a glance. This is what I get from Kosaka’s works. They embrace the artisan spirit of Zen thought and classic aesthetics.’ – Yan Jun, President of Karl Lagerfeld China

Every time you meet with Kosaka’s ceramic works, it doesn’t feel like a first-time encounter; it feels like a reunion.

Returning to the simplicity and innocence of nature, these ceramic vessels serve the purpose entrusted to them. Perhaps the interplay of life and clay is the master’s concept.